Managing Exceptions in BackgroundService or IHostedService Workers

This post applies to .Net 5 and before. .Net 6 introduces a welcome change to exceptions which is detailed here

BackgroundService and its interface IHostedService allow you to define long running services which can be hosted as a stand alone Windows or Linux Service, or as part of a web app or other application. In this post, we will cover proper exception handling for hosted services and take a deeper look into how these services are hosted than is covered in the documentation.

Before getting to some best practices and a sample implementation, let’s take a quick look at the classes and interfaces involved. First is the IHostedService interface. As we can see, this defines StartAsync and StopAsync both of which take cancellation tokens. See the comments in the code for what each token does.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

/// <summary>

/// Defines methods for objects that are managed by the host.

/// </summary>

public interface IHostedService

{

/// <summary>

/// Triggered when the application host is ready to start the service.

/// </summary>

/// <param name="cancellationToken">Indicates that the start process has been aborted.</param>

Task StartAsync(CancellationToken cancellationToken);

/// <summary>

/// Triggered when the application host is performing a graceful shutdown.

/// </summary>

/// <param name="cancellationToken">Indicates that the shutdown process should no longer be graceful.</param>

Task StopAsync(CancellationToken cancellationToken);

}

Next is the Host class (source). This class is responsible for starting each IHostedService instance when Host.StartAsync method is called. If you are interested in more detail on the startup process, an in-depth discussion is available on Andrew Lock’s blog.

For our purposes, the most important part of the startup is line #16 where each registered IHostedService is started, one at a time. Because each StartAsync call is awaited, the time it takes for each service to start will add to the startup time for the application as a whole. Therefore, its important that StartAsync return quickly, which is handled by BackgroundService.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

public async Task StartAsync(CancellationToken cancellationToken = default)

{

_logger.Starting();

using var combinedCancellationTokenSource = CancellationTokenSource.CreateLinkedTokenSource(cancellationToken, _applicationLifetime.ApplicationStopping);

CancellationToken combinedCancellationToken = combinedCancellationTokenSource.Token;

await _hostLifetime.WaitForStartAsync(combinedCancellationToken).ConfigureAwait(false);

combinedCancellationToken.ThrowIfCancellationRequested();

_hostedServices = Services.GetService<IEnumerable<IHostedService>>();

foreach (IHostedService hostedService in _hostedServices)

{

// Fire IHostedService.Start

await hostedService.StartAsync(combinedCancellationToken).ConfigureAwait(false);

}

// Fire IHostApplicationLifetime.Started

_applicationLifetime.NotifyStarted();

_logger.Started();

}

Before going further we should discuss two important aspects of how Task works. The first thing to understand is that when you start a Task it will run synchronously until the called code gets to the an awaited method which is not able to return a result immediately (i.e. we are synchronous until we actually have something to wait for). The second is that if an exception occurs, the exception is bundled into the Task. At this point Task.IsCompleted would be true, and the contents of the Task is now the exception, instead of an expected result or void. When the task is awaited, the exception is then thrown by the await. This is how Tasks propagate exceptions back to the caller, and incidentally, explains why async void is a bad idea.

Lets look at the code below, where we can see this in action. In this example, the following steps occur.

- Log the “Before Starting Task” message

- Start the

Task, running synchronously - Log the “Synchronous Task Execution” message in the

Task - An exception is thrown and wrapped in the

Taskwhich is now complete and returns control toMain, without ever running asynchronously. - Log the “After Starting Task” message.

await badTaskwhich throws the exception whichbadTaskis holding and execution halts.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

using System;

using System.Threading.Tasks;

internal class Program

{

private static async Task Main(string[] args)

{

Console.WriteLine("Before Starting Task");

var badTask = Boom();

Console.WriteLine("After Starting Task");

await badTask;

Console.WriteLine("After Awaiting");

}

private static async Task Boom()

{

Console.WriteLine("Syncronous Task Execution");

throw new Exception();

await Task.Delay(100);

Console.WriteLine("Async Task Execution");

}

}

If we flip the order of the exception and the subsequent delay (lines 19 and 20), then we get this set of steps.

- Log the “Before Starting Task” message

- Start the

Task, running synchronously - Log the “Synchronous Task Execution” message in the

Task - We

await Task.Delay(100). The Delay, of course, takes time to complete andIsCompleteon the delay is false. So, we begin asynchronous execution. TheTaskassigned tobadTaskis not complete. Control returns toMainandbadTask’s delay runs in the background. - Log the “After Starting Task” message.

await badTask. At this point, theDelayis still progressing, so we wait for that. Then the exception is thrown, packaged intobadTaskand is then thrown again by theawaitin theMainmethod.

Notice the status of badTask, when we hit line 10, is complete with an exception in the first case, and is not complete and running asynchronously in the second.

Background Service

With these examples in mind, lets look at BackgroundService.

BackgroundService (source) is an abstract class which implements IHostedService, and isn’t terribly complex. Its key advantage, when compared to implementing IHostedService ourselves, is that it takes care of ensuring that the call to IHostedService.StartAsync returns at the earliest possible moment after starting our code, in our override of ExecuteAsync.

The way this is accomplished is a bit subtle. Notice that when ExecuteAsync is started, but not it is not awaited on line 19. In fact, BackgroundService never awaits our code. This makes sense when we remember that ExecuteAsync could run forever, so we can’t wait for it to finish. The next line checks to see if ExecuteAsync is done running which is true, as we discussed above, in two cases:

- ExecuteAsync contained only synchronous code and has completed its work. This would be a bad use case for

BackgroundService, because our code has blocked the rest of the application from starting for the time it was working. - More likely, an exception was thrown during the synchronous phase of the

Task’s execution. In this case, the task is returned toHoston line 24. BecauseHostawaited the call toStartAsyncit opens theTaskand throws the exception, killing the entire app. In most cases, this isn’t what we would want.

In any case where ExecuteAsync successfully started asynchronous operation then BackroundService returns a completed dummy task on line 28 back to Host which then starts the next IHostedService.

So, what does that mean for _executingTask which is never awaited? Its going to keep running as long as it needs to and if it ever throws an exception we will never know.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

/// <summary>

/// This method is called when the <see cref="IHostedService"/> starts. The implementation should return a task that represents

/// the lifetime of the long running operation(s) being performed.

/// </summary>

/// <param name="stoppingToken">Triggered when <see cref="IHostedService.StopAsync(CancellationToken)"/> is called.</param>

/// <returns>A <see cref="Task"/> that represents the long running operations.</returns>

protected abstract Task ExecuteAsync(CancellationToken stoppingToken);

/// <summary>

/// Triggered when the application host is ready to start the service.

/// </summary>

/// <param name="cancellationToken">Indicates that the start process has been aborted.</param>

public virtual Task StartAsync(CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

// Create linked token to allow cancelling executing task from provided token

_stoppingCts = CancellationTokenSource.CreateLinkedTokenSource(cancellationToken);

// Store the task we're executing

_executingTask = ExecuteAsync(_stoppingCts.Token);

// If the task is completed then return it, this will bubble cancellation and failure to the caller

if (_executingTask.IsCompleted)

{

return _executingTask;

}

// Otherwise it's running

return Task.CompletedTask;

}

Best Practices

Based on the behavior above, we have some clear objectives when we override ExecuteAsync.

- Await something asynchronous quickly, so app startup can continue without blocking.

- Ensure your code cannot ever throw an unhandled exception. Otherwise your service will stop running while the rest of your app continues none the wiser. (Trust me, this isn’t fun.)

- Because we are suppressing exceptions, we will also need to allow for:

- Logging of exceptions

- Back-off may be required if our repeated process should run less frequently when errors are occurring.

- At some point, you may need to trigger some sort of alerting or paging if there are too many failures.

Example Implementation

Below, we will look at an example class, WorkerBase which can accomplish all of these objectives for a service that needs to run on a fixed interval (every few seconds, minutes…). This abstract class is setup so that a class which implements it just needs to override DoWorkAsync. The override of DoWorkAsync should contain all the code that is run periodically, and should throw unhandled exceptions which WorkerBase will handle by logging (and starting a back-off or sending alerts if you add that functionality). An associated interface IWorkerOptions defines how frequently DoWorkAsync is called. Note that the IWorkerOptions.RepeatIntervalSeconds is really defining the time between the end of one run, and the beginning of the next. While this implementation is pretty generic, I left in some simple logging that uses Serilog. The main reason I did that was to point out the value of setting up the instance logger with Log.ForContext("Type", WorkerName);. This means that every log message will contain the name of the class that implements WorkerBase which becomes quite valuable if you have more than one service running in parallel.

You should consider doing your own customization to include back-off and alerting logic discussed above. If you do, I recommend adding any configuration to IWorkerOptions. If adding these features requires injecting additional dependencies, that should be straight forward, but please ask a question below if you run into any trouble.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

/// <summary>

/// Worker provides consistent logging (including a logger enriched with the type of the

/// worker), and alerting. The <see cref="DoWorkAsync"/> method is called indefinetly, so long

/// as it is supposed to.

/// </summary>

public abstract class WorkerBase : BackgroundService

{

private readonly IWorkerOptions workerOptions;

public WorkerBase(IWorkerOptions workerOptions)

{

this.workerOptions = workerOptions;

WorkerName = GetType().Name;

Logger = Log.ForContext("Type", WorkerName);

Logger.Information(

"Starting {worker}. Runs every {minutes} minutes. All options {@options}",

this.WorkerName,

this.workerOptions.RepeatIntervalSeconds,

this.workerOptions);

}

public string WorkerName { get; }

public ILogger Logger { get; }

/// <summary>

/// Work method run based on <see cref="IWorkerOptions.RepeatIntervalSeconds"/>. Exceptions

/// thrown here are turned into alerts.

/// </summary>

public abstract Task DoWorkAsync();

[SuppressMessage("Design", "CA1031:Do not catch general exception types", Justification = "We catch anything and alert instead of rethrowing")]

protected override async Task ExecuteAsync(CancellationToken stoppingToken)

{

// Await right away so Host Startup can continue.

await Task.Delay(10).ConfigureAwait(false);

try

{

while (!stoppingToken.IsCancellationRequested)

{

try

{

Logger.Information("Calling DoWorkAsync");

await DoWorkAsync().ConfigureAwait(false);

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

Logger.Error(

ex,

"Unhandled exception occurred in the {worker}. Sending an alert. Worker will retry after the normal interveral.",

WorkerName);

}

await Task.Delay(workerOptions.RepeatIntervalSeconds * 1000, stoppingToken).ConfigureAwait(false);

}

Logger.Information(

"Execution ended. Cancelation token cancelled = {IsCancellationRequested}",

stoppingToken.IsCancellationRequested);

}

catch (Exception ex) when (stoppingToken.IsCancellationRequested)

{

Logger.Warning(ex, "Execution Cancelled");

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

Logger.Error(ex, "Unhandled exception. Execution Stopping");

}

}

}

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

public interface IWorkerOptions

{

/// <summary>

/// Defines the period between the end of one unit of work and the start of the next.

/// </summary>

int RepeatIntervalSeconds { get; set; }

}

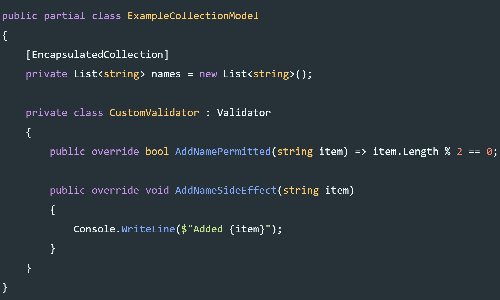

Next is a quick example implementation. There are a few pieces below.

- An example worker,

TimeFileWorker, which writes out a file whose name is the current time. It gets the current time from theITimeServicewhich is in the example as a reminder that your workers can take any dependencies they need, in addition to any which are passed toWorkerBase. TimeFileWorkerOptionsimplementsIWorkerOptionsand also provides the output directory whichTimeFileWorkerneeds.- The corresponding

appsettings.jsonforTimeFileWorkerOptions - Finally, a portion of the

Startupclass for an app using these options.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

public class TimeFileWorker : WorkerBase

{

private readonly TimeFileWorkerOptions workerOptions;

private readonly ITimeService timeService;

public TimeFileWorker(

IOptions<TimeFileWorkerOptions> workerOptions,

ITimeService timeService)

: base(workerOptions.Value)

{

this.workerOptions = workerOptions.Value;

this.timeService = timeService;

}

public override async Task DoWorkAsync()

{

Directory.CreateDirectory(workerOptions.OutputDirectory);

var time = timeService.GetDateTime();

var outFile = Path.Combine(

workerOptions.OutputDirectory,

$"{time:yyyy-MM-dd--HHmmss}.txt");

File.WriteAllText(outFile, WorkerName);

}

}

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

public class TimeFileWorkerOptions : IWorkerOptions

{

/// <inheritdoc/>

public int RepeatIntervalSeconds { get; set; }

/// <summary>

/// Output directory for the <see cref="TimeFileWorker"/>.

/// </summary>

public string OutputDirectory { get; set; }

}

1

2

3

4

5

6

{

"TimeFileWorker": {

"OutputDirectory": "C:\\temp\\TimeFileWorker.WorkerService",

"RepeatIntervalSeconds": 10

}

}

1

2

3

4

5

6

// Example services registration in a WorkerService project.

// The example solution accompanying this post has a web project

// as well.

services.Configure<TimeFileWorkerOptions>(hostContext.Configuration.GetSection("TimeFileWorker"));

services.AddHostedService<TimeFileWorker>();

services.AddSingleton<ITimeService, TimeService>();

An example solution is available which accompanies this post. It includes an example blazor site and worker service which both host the same TimeFileWorker.

Conclusion

Without proper handling, exceptions in IHostedService can be difficult to detect. This post discussed why this occurs and provided an example implementation you can use as a starting point to keep your services from silently failing.

Comments

Leonid

Can you use

Task.Yield()instead ofTask.Delay()?Mike Conrad

@Leonid,

It looks like

Task.Yield()works fine. To test it I took my sample project and added a synchronous wait usingThread.Sleep(10000)to the worker. Callingawait Task.Yield()here: https://github.com/Siphonophora/BackgroundServiceExceptions/blob/test-task-yield/BackgroundServiceExceptions.Core/WorkerBase.cs#L50 allowed the service to finish initializing without waiting for 10 seconds.I tried

await Task.CompletedTaskand that version did take the extra 10 seconds to start up.granadacoder

Thank you for the in depth look. Excellent work.

(Nit picks my compiler found : “Unhandeled” is misspelled. Cancelation is misspelled.)

Please don’t let those nitpicks deter from the excellent deep thinking on this.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *